Have you ever spent forty hours of your life meticulously crafting a crochet sweater, only to try it on and realize you’ve essentially built a cardboard box made of yarn? You stand in front of the mirror, hoping that a good steam block or a “strategic tug” will fix it, but deep down, you know the truth: you aren’t wearing a garment; you are wearing a soft suit of armor. It’s stiff, it’s bulky, and it moves with all the grace of a tectonic plate.

Why does this happen? Why is it that knitting—crochet’s thinner, more popular cousin—seems to produce effortless, flowing cardigans, while crochet often results in something that looks like it could stand up on its own in the corner of the room? Is it a curse inherent to the craft? Is the “double loop” of the crochet stitch simply too structural for fashion? The answer, as it turns out, is a mixture of physics, fiber chemistry, and a few lies we’ve been told by big-box yarn manufacturers. If you are ready to stop wasting your time on “wearable blankets” and start creating actual fashion, we need to talk about the science of drape.

The Structural Curse of the Crochet Stitch

To solve the mystery of the stiff sweater, we first have to look at the anatomy of the stitch itself. A knit stitch is essentially a series of interlocking loops that create a thin, flexible mesh. It’s a one-dimensional structure. A crochet stitch, however, is a knot. Whether you are making a single, half-double, or double crochet, you are wrapping yarn around itself, creating a multi-layered, three-dimensional pillar of fiber.

When you combine thousands of these tiny pillars, you aren’t just making a fabric; you are building a wall. Because the yarn is wrapped around itself, it consumes nearly three times as much material as a knit stitch of the same size. More yarn equals more weight, and more weight—if not managed correctly—equals stiffness. Have you ever wondered why your swatch feels soft, but the finished sweater feels like a rug? It’s because gravity is pulling on that extra weight, compressing the stitches and locking them into a rigid grid. Are you building a bridge, or are you making a blouse?

The Hook Size Lie: Why You Need to Go Bigger

One of the most common mistakes beginners (and even intermediates) make is following the hook size recommended on the yarn label. That little icon on the back of the skein is a suggestion for a “standard” fabric, often intended for blankets or hats where structure is a benefit. If you use a 5mm hook for a Worsted weight yarn to make a sweater, you are almost guaranteed a stiff result.

The secret that professional designers won’t always tell you is that drape is born in the gaps between the stitches. To get drape, you need air. You need space for the “pillars” of your crochet stitches to lean, bend, and move against one another. To achieve this, you must often go up two, three, or even four hook sizes from what the label suggests.

If you aren’t slightly uncomfortable with how “loose” and “holey” your work looks while it’s on the hook, you probably aren’t using a large enough size. When the garment is finished and washed, those gaps will settle, and the weight of the yarn will pull the stitches down, closing the holes and creating that elusive, liquid movement. Are you brave enough to trust the air?

The Fiber Hierarchy: Not All Yarn is Created Equal

If you are trying to make a flowing summer duster out of 100% “value” acrylic, you are fighting a losing battle. Acrylic is a polymer—plastic. It has “memory,” which is a fancy way of saying it wants to stay in the shape it was manufactured in. While high-end micro-acrylics have improved, the budget-friendly stuff is inherently rigid.

To achieve real drape, you must look at the molecular weight and the “slip” of your fiber. This is where the experts separate themselves from the crowd.

The Heavy Hitters: Silk, Bamboo, and Rayon

If drape is your primary goal, these three fibers are your best friends. Bamboo and silk are heavy, but they have a “slippery” surface. In crochet, this is vital because it allows the yarn to slide within the knot of the stitch. When you move, the yarn moves. It doesn’t “catch” on itself.

Have you ever touched a bamboo crochet top and noticed how it feels cold and heavy, yet it flows like water? That is because plant-based silks have zero “memory.” They don’t want to stand up; they want to fall down. If you want a sweater that hugs your curves instead of hiding them, you have to choose a fiber that understands gravity.

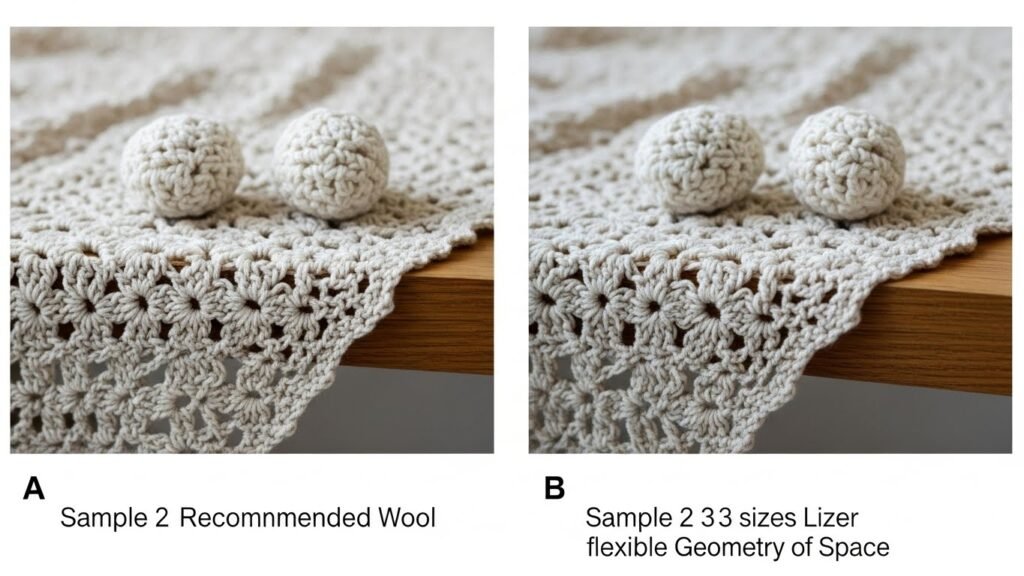

The Wool Problem: Why Merino Isn’t Always the Answer

We love Merino wool for its softness, but it is a “crimped” fiber. It’s bouncy. It’s full of air. While this is great for a cozy winter toque, that bounce creates “loft,” and loft is the enemy of drape. If you must use wool, look for a “Superwash” variety. The chemical process that makes wool machine-washable also flattens the scales of the fiber, making it slicker and heavier. It’s a rare case where the “processed” version is actually better for the fashion-forward creator.

Gravity as a Tool: The Weight of the Hem

Think about the most expensive dress you’ve ever seen. It doesn’t just sit on the body; it pulls toward the earth. In crochet design, we can use the weight of the yarn to our advantage. If your sweater looks a bit stiff at the waist, adding a heavier ribbed hem or a decorative border can act as a “weight” that pulls the stitches above it into a vertical alignment.

This tension is what creates the “vibe” of a professional garment. Without that downward pull, the stitches stay in their natural, square-ish state, creating that “armor” effect. Are you designing your hems to be pretty, or are you designing them to be functional anchors for your drape?

Stitch Selection: The Death of the Single Crochet

If you want a sweater that drapes, you have to banish the solid Single Crochet (SC) from your garment vocabulary. The SC is the densest, most rigid stitch in the repertoire. It is the brick of the crochet world. If you build a house of bricks, don’t be surprised when it doesn’t move in the wind.

To get movement, you need height. Taller stitches, like the Double Crochet (DC) or the Treble Crochet (TR), have more “leg” to them. That “leg”—the vertical part of the stitch—acts like a hinge. The longer the hinge, the more the fabric can fold and sway.

The Magic of the “V-Stitch” and the “Linen Stitch”

If you want the look of a solid fabric without the rigidity, you have to use “broken” stitches. The V-stitch (DC, ch 1, DC) creates a trellis-like structure that is incredibly flexible. The Linen Stitch (also known as Moss Stitch), despite using SC, incorporates chain spaces that act as joints, allowing the fabric to remain thin and supple.

Why are we so obsessed with “solid” stitches when a slightly open fabric creates such a better silhouette? Are we afraid of what’s underneath, or are we just following outdated patterns that haven’t evolved with modern fashion?

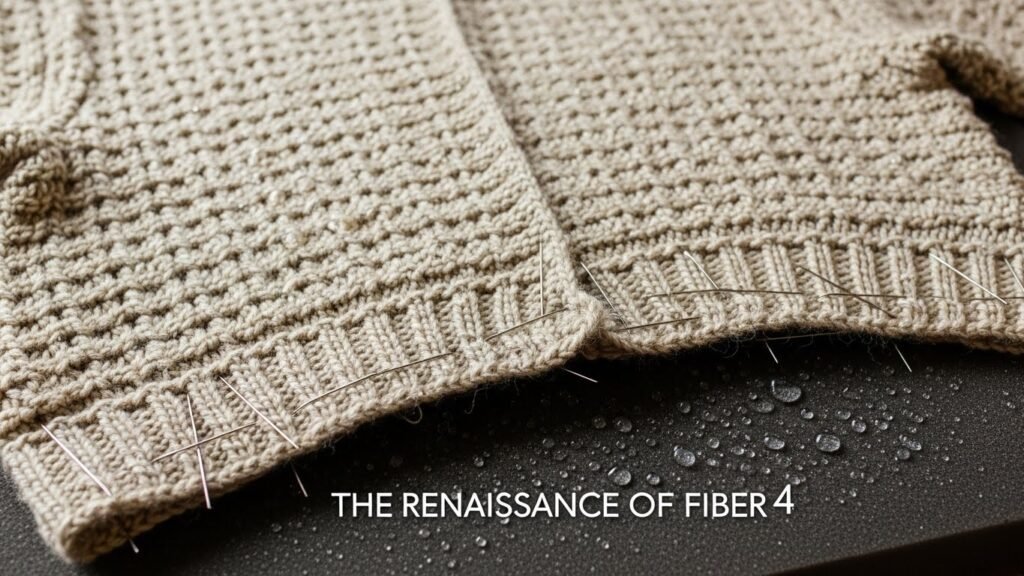

The Blocking Ritual: Your Final Opportunity for Redemption

You’ve finished your sweater. It’s still a bit stiff. This is the moment of truth. Many crafters skip blocking because it’s “boring” or “takes too long.” But if you want drape, blocking isn’t optional; it’s a chemical and physical necessity.

When you submerge your sweater in water, the fibers relax. The tension you held in your hands while crocheting is released. For natural fibers, this is where the “bloom” happens. The stitches settle into their neighbors, the gaps close, and the yarn loses its manufacturing stiffness.

Steam Blocking: The Secret Weapon for Acrylic

If you did use acrylic, a light “kill” blocking with steam can transform the plastic. By applying heat (without touching the iron to the yarn!), you are slightly melting the outer layer of the fibers, causing them to lose their “memory” and relax forever. It is a one-way trip to Drape-Ville. But be careful—once you “kill” acrylic, you can never get the bounce back. Is that a sacrifice you are willing to make for a sweater that finally fits?

The Gauge Swatch: Your Insurance Policy Against Armor

I know, I know. You hate swatching. We all do. But if you are making a garment, a swatch is your only way to test the “Drape Factor” before you commit weeks of your life to a failure.

Don’t just measure your stitches per inch. Take that 4×4 inch square and hold it in the palm of your hand. Does it stand up like a piece of toast, or does it flop over your fingers like a pancake? If it’s a piece of toast, you need a bigger hook. If it’s still a piece of toast, you need a different yarn.

Why do we treat swatching like a chore instead of a scientific experiment? It is the only time in the entire process where you have total control over the outcome. Once the sweater is finished, the physics are set in stone. Wouldn’t you rather know the truth now?

Conclusion: Designing for Movement

Crochet has been unfairly maligned as a “stiff” medium for too long. We have the tools to create garments that rival anything found on a Parisian runway, but we have to stop thinking like blanket-makers and start thinking like textile engineers.

Drape is not an accident. It is the result of intentional choices: a larger hook than you think you need, a fiber with significant molecular weight, stitches with height and air, and a finishing process that respects the relaxation of the yarn.

Are you ready to stop hiding behind your armor? Are you ready to let your crochet move, breathe, and dance with you? The next time you pick up your hook, don’t just think about the pattern. Think about the air. Think about the gravity. Think about the flow. Your wardrobe will thank you, and your “armor” can stay where it belongs—in the history books.

My name is Sarah Clark, I’m 42 years old and I live in the United States. I created Nova Insightly out of my love for crochet and handmade creativity. Crochet has always been a calming and meaningful part of my life, and over the years it became something I wanted to share with others. Through this blog, I aim to help beginners and enthusiasts feel confident, inspired, and supported as they explore crochet at their own pace. For me, crochet is more than a craft — it’s a way to slow down, create with intention, and enjoy the beauty of handmade work.